Global food security in the context of global warming

According to the United Nations (UN), around a tenth of the world’s population is facing malnutrition. How can global food production adapt to a constantly growing population and the challenges posed by global warming?

Global warming, which humans have been causing since the start of the industrial era (at the beginning of the 20th century) is a threat which affects the whole human population across the entire world. The press release from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) begins with these words on the evening of 27 February 2022. On this day, the group of scientists presented the second part of its sixth assessment report on global warming. In this report, which contains over 3,600 pages, the consequences (both present and future) of climate change on the Earth, the areas of vulnerability and the ways in which we can adapt are discussed. “This report issues a very serious warning about the consequences of inaction,” points out Hoesung Lee, President of the IPCC.

A few weeks later, on 4 April, the third and final part of the sixth IPCC report was published. This part provides an updated global assessment of past and present greenhouse gas emissions and possible progress and commitments to mitigate global warming. It provides outlooks and options for reducing emissions in key sectors (energy, transport, buildings, industry, agriculture, land use and food, etc.). According to the experts at the IPCC, even though global warming has already had irreversible effects on the planet’s environment, there is still time to act and protect the future of humanity. But this is on the condition that action is taken now: if greenhouse gas emissions do not stop rising within three years, and if they have not been halved from current levels by 2030, the temperature increase by the end of the century will irrevocably exceed +1.5°C compared to the pre-industrial era. And future living conditions will be significantly worse for all humanity.

The fifth chapter in this second part of the report deals more specifically with food produced from ecosystems. The IPCC highlights the impact, which is already apparent, of climate change on global agri-food systems which have plunged hundreds of millions of people into food insecurity. According to the experts of the third working group of the IPCC, agriculture, forestry and other land uses accounted for between 13% and 21% of human greenhouse gas emissions between 2010 and 2019. The group of scientists explains that the global food system is currently failing to address issues of food insecurity and malnutrition in an environmentally sustainable manner. Whether directly or indirectly, climate change is affecting the world's crops and the four pillars of food security (accessibility, availability, use of food and stability of supply).

How climate change affects crops

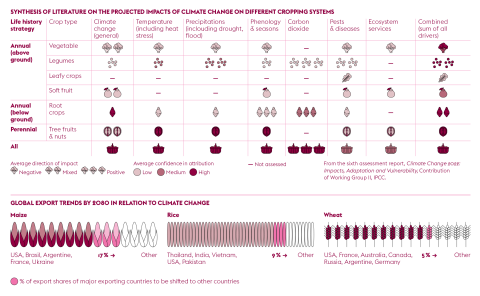

According to the latest report from the IPCC, the number of factors affecting world food production as a result of global warming are numerous. The group of researchers from 195 countries have found that climate change has already had a major impact on crop yields, their quality and marketability. “There is moderate evidence and a broad consensus that the effects of human-induced global warming since the pre-industrial era have had significant negative consequences on global agricultural production, acting as a brake on the growth of such production,” write the IPCC experts in their report. The scientists cite several studies which support this, including one showing that total factor productivity (TFP), which combines all crop productivity coefficients, was reduced by 21% between 1961 and 2015 despite the many technological advances over the previous decades. These effects vary according to the region in the world. Compared to a model excluding the consequences of human-induced global warming, TFP falls by 30-33% in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, for example.

The IPCC experts report that the reasons for this loss in productivity are manifold. First and foremost, the number of unpredictable weather events (droughts, cyclones, etc.) is increasing. If the climate projection ‘fossil-fuel based development (SSP5-8.5)’ scenario is followed, “Overall, 10% of areas currently suitable for large-scale crop and livestock production will become unsuitable in terms of their climate by 2050, and between 31% and 34% of these areas by the end of the century,” the IPCC warns. Heat waves and periods of drought are increasing and these events impact agriculture either directly or indirectly, with crops dying, or planting becoming impossible or delayed. In Europe, crop losses from these two types of catastrophic event have tripled in the last 50 years, the IPCC reports. Flooding is also increasing across the globe. The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) estimates that the flood which devastated Pakistan's crops in 2010 is equivalent to a loss of more than €4 billion for local farms. The Sahel region of Africa has suffered some of the worst periods of variation in rainfall over the decades, with twenty years of heavy rains followed by twenty years of drought greatly reducing the cultivation capacity of the region between 1950 and 1990.

In addition to the increase in natural disasters, global warming has also led to an increase in weeds on farms. These have always had the capacity to ravage crops (grains, grazing and forestry), but scientists at the IPCC have shown that global warming favours their increase due to several criteria.

First and foremost, these invasive plants are more likely to grow in places where there are higher levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) and higher temperatures, according to a recent meta-analysis cited by researchers at the IPCC. However, the scientists note that the growth of such plants in regions with areas of low fertility offers interesting opportunities. The concentration of CO2 also changes the biochemistry of plants, making weeds more resistant to herbicides, for example. Climate change and the physical changes it brings to the environment (e.g. changes in precipitation rates) directly damages the quality of the distribution of herbicides.

Extreme changes in rainfall rates also have an impact on the quality of the soil in which crops are grown. According to the IPCC, these reduce the effectiveness of the soil biology and increase the risk of flooding, waterlogging and land erosion. The rise in sea level is another danger for soil balance and is the cause of the acidification and increased salinity of coastal soils, which has already killed many crops.

The IPCC Working Group II has created a non-exhaustive list of consequences (both direct and indirect) of global warming on world agriculture. “Food and nature interact in complex ways through political, economic, social, cultural and demographic factors, leading to issues of food security and sustainability,” the scientists write at the start of chapter 5 in the report. The response to combat these changes, which today are driving hundreds of millions of human beings towards food insecurity, will have to be global.

Are there other ways to cultivate land?

We will have to change how we cultivate the land in order to alleviate the drop in crop yields resulting from global warming. For David Makowski, who works at the Applied Mathematics and Computer Science unit (MIA – Univ. Paris-Saclay, INRAE, AgroParisTech), agroecology is one of the solutions to be explored. Moreover, the IPCC scientists make the same observation: in the third part of their sixth report, agro-ecology is presented as a viable solution to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector. “It’s a current trend which aims to harness the natural resources necessary for agricultural production by limiting the use of chemicals to a minimum,” explains the researcher. “This involves finding all the natural means possible to limit the use of fertilisers and pesticides, etc. For example, species such as legumes which fix nitrogen from the atmosphere can be used, as well as biological control methods which limit the impact of crop-damaging diseases while using as few environmentally harmful chemicals as possible.” Agroecology is a combination of practices which aims to preserve the environment while maintaining a high level of agricultural output. “In reality, it’s difficult, however, to achieve no yield loss at all with agroecological practices compared to crops using a range of chemical products,” observes David Makowski.

Conservation agriculture is a farming method which has been proposed in this context. “It’s a specific system which combines three practices, i.e. no tilling, crop rotation (at least three crop species grown in rotation) and maintenance of plant cover for the soil. Conservation agriculture has been the focus of numerous trials in many regions across the world for different reasons. These are both economic (the lack of tilling means farmers expend less energy and save time) and ecological (improvement in soil quality). In principle, conservation agriculture means more carbon is locked into the soil, the soil’s biodiversity is improved and the risk of erosion is reduced,” explains David Makowski.

Conservation agriculture has attracted a lot of attention, some of which goes against the founding ideals of this type of farming practice. “This system is associated with the use of genetically modified crops on the American continent. These are resistant to glyphosate, a very powerful herbicide. Tilling basically kills weeds. When no tilling takes place, the weeds grow much more easily, start to compete with the crop and reduce yields,” explains David Makowski. To manage this problem, manufacturers proposed the use of glyphosate, which required the development of glyphosate-resistant crops. This has been achieved by genetically modifying certain crop species, such as maize and soybeans. “It’s a real ‘technological package’ which has been developed involving no tilling, combined with genetically modified crops and glyphosate. This has worked very well and was quickly applied on a very large scale in North and South America. It’s a bit of a paradox because this system of conservation agriculture has been championed by agribusiness as a way of producing crops on a large scale and intensively, but has also been championed by agroecology advocates who have ideals to do with environmental protection.”

In his latest work based on the meta-analyses of data obtained from agroecological production systems, David Makowski has looked at the success different agricultural practices have in achieving high yields while limiting the environmental impact they make. “To what degree can we limit the risk of water pollution or greenhouse gas emissions? To what degree can we increase biodiversity in agroecological systems?”

Adapting crops to climate change

Global warming has already altered the planet and global agricultural systems. Rising temperatures have dried some countries, drastically reducing their capacity for agricultural production. “There will be winners and losers,” explains David Makowski. “It’s clear that there will be major problems caused by global warming, but also opportunities. The question is, what will they be and how can we make the most of them?” Regions in the world where growing cereal crops was difficult in the 20th century have already profited from the rise in temperatures. Ukraine and Russia, for example, have become important wheat producers over the past years, and this is partly thanks to global warming. In light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it is important to stress that war and food insecurity go hand in hand. Russian aggression will have a strong impact on the supply of agricultural raw materials, particularly in North Africa and the Middle East.

Several strategies already exist for adapting to climate change. The rise in temperatures has already made it possible to increase the number of annual harvests in some regions (on average, two to three rice harvests per year take place in South Asia). Plant breeding is also being studied to ensure that the best species are grown for the changing climate. “Adapting to climate change should be some of the strategies to consider,” points out Christophe Gouel, who works at the Paris-Saclay Applied Economics Laboratory (PSAE - Univ. Paris-Saclay, INRAE, AgroParisTech). “When we talk about adapting agriculture, we’re talking about the development of new drought-resistant seeds, the construction of dams to irrigate crops, etc.” However, we often forget that adaptation can also be achieved via agricultural markets. In his recent work, the researcher addresses the question of the global changes in diet which will occur.

Farmers throughout the world will be encouraged to plant different crops both because of differences in yields due to climate change as well as changes in prices. According to simulations by Christophe Gouel, the role the market plays in how agriculture adapts to global warming will be essential. Without this adaptation “there are significant losses due to climate change, but these are even greater if changes in the flow of trade are prevented. It is also shown that as a result of climate change, significant trade changes will take place. Certain countries with a history of exporting will lose this role. However, countries where the climatic conditions are the most extreme today, such as Argentina, will become the greatest producers. There will be significant change in how trade is shared out.”

Finding answers to food insecurity

Would it be possible to feed the world’s population, a large part of which is already at risk of food insecurity, as the effects of global warming increase? “Theoretically speaking, the results put forward by the literature say yes,” says David Makowski. “It would be difficult without intensifying agriculture, at least in certain geographical zones where agriculture is currently relatively extensive, such as the African continent for example. This would be much easier as our diets evolve - in particular if we eat less meat. Populations are increasing and so is the demand for food, but there is still some room for improvement, especially in terms of yields. Also, as regards climate change, there’s room for improvement in terms of increasing the amount of land available for cultivation in areas which are currently difficult to cultivate due to low temperatures. In terms of food security, I think the overall picture of the scientific findings is that we should be fine.”

As the IPCC and the FAO have shown, if nothing is done about adapting to global warming, it will worsen the global food insecurity situation, which affects nearly 800 million people already, according to the UN. It is no longer a question of preventing global warming, but more of adapting to its effects on the planet and our way of life.

Publications:

IPCC WGII. Sixth Assessment Report – Chapter 5: Food, Fibre, and other Ecosystem Products. 2022.

Su, Y., Gabrielle, B. & Makowski, D. A global dataset for crop production under conventional tillage and no tillage systems. Sci Data 8, 33, 2021.

Gouel C., Laborde D. The crucial role of domestic and international market-mediated adaptation to climate change. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, Volume 106, 2021.