Semi-precious stones - evidence of prehistoric skills and expertise

Myanmar (Burma), currently in the midst of turbulent events, is a Southeast Asian country whose past still holds many secrets. Thanks to the semi-precious stones found in funerary ornaments, scientists are able to trace the economic and social exchanges which marked this region of Asia towards the end of the prehistoric period.

The only Southeast Asian country to share land borders with India and China, Myanmar (Burma) is a major centre for economic and social exchange and this contributes to the country's cultural wealth. Nevertheless, its ancient history remains a deep mystery. Written evidence left by earlier civilisations provides us with descriptions of an important period, but they do not allow us to go back beyond the first century AD. Only archaeology is able to describe prehistoric Myanmar. Still largely unexplored, the remains of ancient Burmese civilizations nevertheless represent an important chapter in Southeast Asian history.

In order to explore this area further, the Burmese authorities and CNRS set up a scientific partnership in 2001 and launched the ‘Mission archéologique française au Myanmar (MAFM - French archaeological mission in Myanmar), financed by the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs. Through archaeological excavations, it aims to uncover the evolution of the Burmese people from the time of the hunter-gatherers (3rd millennium B.C.) to the creation of the first states (1st millennium A.D.). T. O. Pryce, a research associate at the “Laboratoire archéomatériaux et prévision de l’altération” (LAPA - Archaeomaterial laboratories and weathering prediction) at the “Institut de recherche sur les archéomatériaux” (IRAMAT - Research Institute for Archaeomaterials) and the laboratory “Nanosciences et innovation pour les matériaux, la biomédecine et l’énergie” (Nanosciences and innovation for materials, biomedicine and energy) (NIMBE - Université Paris-Saclay, CEA, CNRS), has been leading it since 2012.

Funerary ornaments, semi-precious stones and cultural exchange

The researcher and his team are interested in the funerary practices of the Burmese people and the remains associated with them. The specialists are concentrating their study on semi-precious ornaments in particular. These funerary ornaments, placed near the deceased in their burials, give a lasting insight into the local population’s ceremonies.

Analysis reveals the techniques used to create them, through which the scientists can then infer cultural practices. By comparing them with those of surrounding regions, they can identify the economic and social exchanges which are at the root of any changes in the ceremony.

These semi-precious ornaments are frequently studied by archaeologists and are also historical markers. An example of this is certain types of carnelian beads, traditionally associated with the beginnings of economic exchanges with South Asia at the beginning of the Iron Age (5th century B.C.). The way in which they have been shaped shows the craftsmanship found in India at that time. However, a recent archaeological expedition has proved to be a real game-changer. It has shown that carnelian beads found in remains in the centre of Myanmar dating from the Neolithic period (end of the 2nd millennium BC) attest to an earlier expertise.

The secret of the burials in the heart of Myanmar

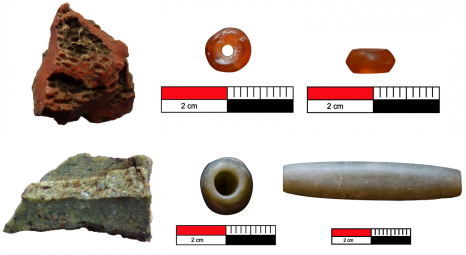

Team members have extracted a total of 489 beads from funerary ornaments from sites across the central region of Myanmar and have noted three key shapes - discs, cylinders and truncated ellipses. The scientists have established that the orange and red discs and the cylinders were cut from a hard stone (carnelian and quartz), while the truncated ellipses, with green, grey or black tones, were cut from a soft stone (nephrite, talc and andesite). They then carried out a technological study of the ornaments (i.e. the marks left on their surface by the objects and handiwork skills used) to reconstruct the “operating chain” used in their manufacture. They found that the craftsmen first removed the excess material necessary to create a bead, then gave it the desired shape, perforated it and finally gave it its finishing touches (polishing, engraving).

By comparing these manufacturing techniques with those known for the same period, scientists were able to trace them back to the social group which used them. “It is meticulous and scientific work which aims to classify the production of funerary ornaments according to the skills of the craftsmen themselves,” points out T. O. Pryce. Any change in the “modus operandi” makes it possible to monitor cultural and social exchanges between different populations.

Local Burmese production

The study set up by T. O. Pryce’s team has shown that all the beads uncovered were made at the same production site of Nyaung’gan and that their simple-shaped design was of indigenous origin. “Their production was actually local and the raw material was probably found in the region,” explains the researcher.

This result reveals that at the end of the 2nd millennium/beginning of the 1st millennium B.C., central Myanmar was not as yet engaging in economic trade with South Asia. It also calls into question knowledge about prehistoric Burmese skills and expertise, since the crafting of funerary ornaments set with carnelian beads in simple shapes had already been mastered in Myanmar.

In short, the economic and social life of prehistoric regional populations is much more complex than it seems, and still retains some mystery. In order to shed some light on this, T. O. Pryce’s team are currently conducting a study on the protohistoric site at Halin within the city of Pyu, which has been listed by UNESCO. There, the ruins may tell a new chapter in Burmese history over a period extending to the Neolithic period.

Photographs of stones (left) and beads (right) in semi-precious rock: above a carnelian disc and below a truncated nephrite ellipse. - © Mission archéologique française au Myanmar.

Source :

Georjon, C., Kyaw, U. A. A., Win, D. T. T., Win, D. T. T., Pradier, B., Willis, A., Petchey, P., Iizuka, Y., Gonthier, E., Pelegrin, J., Bellina, B., Pryce, T. O. Late Neolithic to Early-Mid Bronze Age semi-precious stone bead production and consumption at Oakaie and Nyaung’gan in central-northern Myanmar. Archaeological Research in Asia, 25, 100240 (2021).