Subcutaneous chemotherapy, a solution to ease cancer treatment?

With ten million deaths each year, cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. While there are treatments, such as chemotherapy, they often cause very painful side effects for patients and involve many logistical constraints. Researchers at Université Paris-Saclay have developed a new type of chemotherapy that can be administered subcutaneously. The aim is to make this therapy more comfortable, more effective, and thus revolutionise cancer treatment.

Cancer is the leading cause of premature death in France. Every year, nearly 400,000 new cases are identified on average in France, and there are over 150,000 cancer-related deaths over the same period. Worldwide, more than 18 million cases are detected annually, resulting in nearly 10 million deaths. These figures alone explain the research efforts undertaken against this disease.

Cancer is characterised by the excessive and uncontrolled proliferation of cells whose DNA, the carrier of genetic information, has certain mutations. This uncontrolled mass then forms a malignant tumour. However, in reality, there are many different types of cancer, named according to the original location of the first tumour. There are currently many therapies used to fight cancer. Excision, a surgical procedure to remove the tumour, is the preferred method. When such a procedure is no longer feasible, for example when there are too many tumours, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are required. These two treatments rely on the use of ionizing radiation and the administration of various active ingredients respectively in order to destroy cancer cells.

Of all the cancer therapies, chemotherapy is surely the most invasive. In the vast majority of cases, it consists of a central intravenous injection (i.e. directly into a large vein) during long sessions in hospital. It is a painful, long, costly and demanding treatment for both patients and medical staff. Many of the active ingredients used in chemotherapy are also irritant and vesicant (causing tissue damage); side effects such as hair loss or toxicities (haematological, cardiac or neurological) are also observed in people during their treatment.

Neutralising the irritant and vesicant nature of chemotherapy

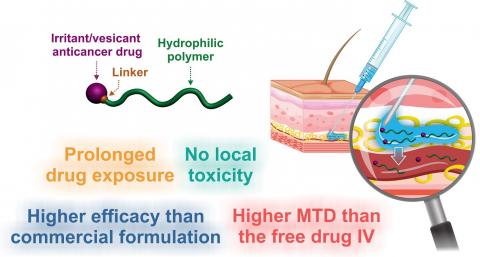

Within the Galien Paris-Saclay Institute (IGPS - Univ. Paris-Saclay, CNRS), in association with the Saclay Nuclear Research Centre (CEA Paris-Saclay) and the federation of Oniris veterinary analysis laboratories (LabOniris), researchers from the Nanomedicines for the Treatment of Serious Diseases and Particle and Cellular Engineering for Therapeutic Purposes teams want to rethink chemotherapy and its approach. To do this, they have set themselves the objective of bypassing the intravenous route in favour of the administration directly under the skin (subcutaneous) of a prodrug of their own making, a nanomedicine composed of a water-soluble polymer linked to an anti-cancer molecule.

This coupling has the benefit of neutralising the toxicity of the active ingredient during its migration through the subcutaneous tissue to the bloodstream, where various enzymes will then break the bond between polymer and active ingredient. "Most anti-cancer molecules are irritant and vesicant. And most of them are also hydrophobic, which results in a subcutaneous stagnation of the drug. By linking the active ingredient to a hydrophilic polymer using a covalent bond, the whole becomes soluble, and the irritant and vesicant nature of the prodrugs is temporarily 'turned off'," explains Julien Nicolas, CNRS Director of Research at IGPS.

The prodrug designed by the team members consists of polyacrylamide and paclitaxel (Taxol®), a hydrophobic anti-cancer molecule that is highly vesicant and commonly used to treat different types of cancer. "Schematically, we 'grew' the polyacrylamide from the paclitaxel. The concept itself is quite interesting," says Julien Nicolas. Using this synthesis technique, IGPS scientists control the length of the polymer and the nature of the bond with the active ingredient. "We chose this polymer specifically for its biocompatible and hydrophilic characteristics. Once the polymer has reached a certain length, a water-soluble prodrug is obtained which can be injected subcutaneously, without observing any stagnation or damage to the skin or subcutaneous tissue. To do this, we need a paclitaxel-polymer bond that is strong enough to prevent any early release of the active ingredient, but fragile enough to be cut by the enzymes in the bloodstream," explains the chemist. Once the bond is broken, the polyacrylamide is eliminated by renal filtration.

In addition to paclitaxel, the team members have already tested their methodology on other anti-cancer molecules. "From a synthesis perspective, our process is adaptable, with enough versatility, to other active ingredients, both hydrophilic and hydrophobic. They just have to be modified to allow the polymer to grow," adds Julien Nicolas.

A less painful... and more effective administration?

Compared to standard intravenous injection methods, the subcutaneous administration of chemotherapy is more comfortable for patients, requires limited medical staff throughout the treatment, and is also more effective in fighting tumours, according to Julien Nicolas. " Polyacrylamide has stealth properties with regards the immune system. Consequently, the prodrug has a prolonged residence time in the bloodstream and acts as a reservoir for paclitaxel. Indeed, we realised that the molecule is released gradually in the blood. And this is an advantage."

So, given the gradual nature with which the active ingredient is delivered, it is possible to see an increase in the time patients are exposed to their chemotherapy, as Julien Nicolas explains. "The polymer will spend some time in the bloodstream before being eliminated naturally. The maximum concentration of the active ingredient in the body is the cause of most undesirable side effects. Unlike the intravenous route, with the subcutaneous injection of our prodrugs, this maximum concentration is much lower. This means that the effect of the treatment is spread over time. As a result, the injected dose can be increased without risk of toxicity," says the researcher.

Many challenges now await the IGPS team. After conclusive results obtained in an animal model (mice), we must now turn to clinical studies in humans. The start-up Imescia, recently created based on the laboratory's research, aims to raise funds (up to 2.5 million euros, according to Julien Nicolas) and start the first clinical trials in 2024.

Publication

A. Bordat et al. A Polymer Prodrug Strategy to Switch from Intravenous to Subcutaneous Cancer Therapy for Irritant/Vesicant Drugs, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.2c04944